Reprogramming Domesticity

Speculation on Alternative Public Space

* The essay was wrote for class “Gender, Sexuality, and the Built Environment” in 2018

How can the discipline of architecture guard its freedom to speculate? … How can experimental architecture open itself to an expanded real of action? … Do we recognize space as a key problematice of our time? How do we build spatial consciousness and develop knowledge of the basics? … What can architecture become?

-- Henry Urbach Agitate for Architecture

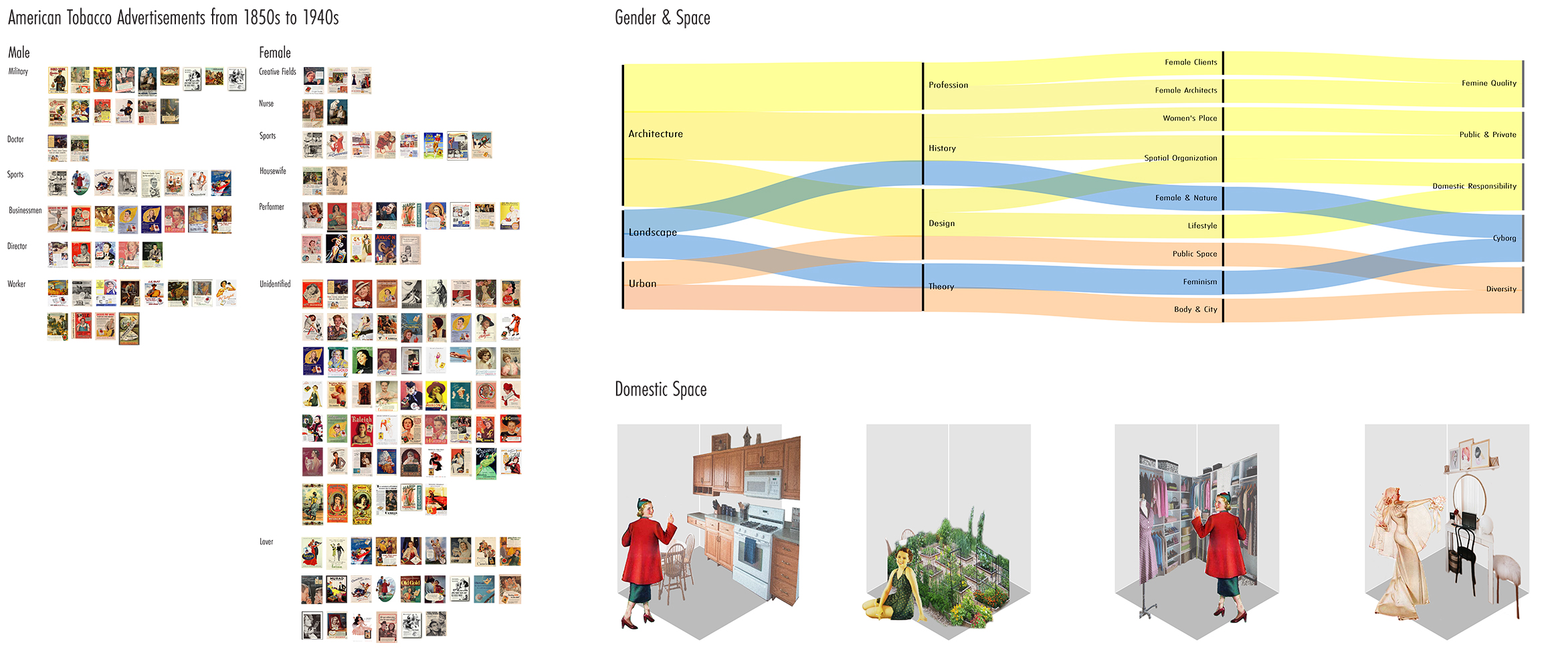

In this essay, I intended to discuss one of my academic projects during a research studio in 2017. The main theme I explored in this project is the concept of the home as a social construction, but also as a space to perpetual social relations. The design project serves as a case study to examine the problematic aspect of the home and to propose a new typology of space to form non-hierarchical social relations. There are three sections in this essay, the first section is Exhibition of Current Relations, in which I will discuss the idea of home in general and how it works to reinforce inequality in gender and social roles. The second section is a description of my design project interweaving with the analysis of it as a deconstruction of the idea of the home. The final section is to explore some of the ways people might use spaces and therefore draw out the possibilities for architectural design to speculate new progressive forms of spaces.

Exhibition of Current Spatial Relations

Architecture programmatic function is always associated with specific spatial configuration - schools have classrooms, libraries have reading rooms, homes have bathrooms and bedrooms, etc. The types of building have become more and more standardized because of the mass production of building materials and conventions in the building industry. As a result of the lack of variety of spaces, there are only certain codes of behavior is deemed appropriate and acceptable in certain spaces. People have to behave in particular ways or obey particular rules in order to occupy particular spaces. The restriction for people’s behavior can be especially problematic because the way spaces are constructed by the privileged class and gender. In order for an individual to inhabit a space, the individual is forced to conform into the norm imagined by the dominating class and gender. Space, as many anthropologists argue, is inherently political and social. Doreen Massey states, “It is not just that the spatial is socially constructed; the social is spatially constructed too”(Massey 1984).

A home, especially in Western societies, is a symbol of many contradictory things. The condition and location of the house can indicate which social class the owner belongs to, whether is lower class or higher class. A house shows the mastery of the owner over his (or hers) the family as a private domain. Household management is basically the ability to assign every detail of daily life into specific places. Therefore, the spatial arrangement within a house is a manifestation of spatial economy. A house is not a space of confrontation, instead, it is created to be as frictionless as possible. In order for the house to reinforce the “natural” relationship for people inside the house, it restrains its users to perform in particular ways. The house can invoke a sense of security and comfort for some, and for others, it might represent suffocation and restraint.

It is a common understanding that women are more associated with the home and private sphere, and men are more associated with the public realm. Even within feminists discussion, the paradigm of the ‘separate spheres’ is a pervasive representation of gendered spaces (Rendell 2000, 103). Daphne Spain in Space and Status fiercely argue that the social status of women and men are spatially constructed by home and institutions. The ability of feminist geographer to “reveal the spatial dimension of gender distinctions that separate spheres of production from spheres of reproduction and assign greater value to the productive sphere (Spain 1992, 7)” is incredibly valuable in terms of uncovering the problematic assumption hidden in spaces. However, this ideology can be too simplified and compartmentalized for the actual complexity of gendered spaces. As many other feminist theorists such as Susana Torre and Elizabeth Wilson argue, this dominating intellectual framework is most constructive as an entry point for “critiquing the limited definitions of gendered space offered by the separate spheres ideology and providing alternative ways for thinking about how space is gendered (Rendell 2000, 103)”.

Deconstruction of Current Spatial Relation

The design intent of the Reprogramming Domesticity is using the concept of home as a lens to enter a broader discussion of freedom and regulation, public and private, exclusive and inclusive spaces. The project operates on the idea of home as a private sphere to questions the arbitrary division of public and private, and provide new ways of thinking about public space through the deconstruction of the home.

From a distance, visitors see multiple floating house shape spaces fixed by scaffolding-like steel structures. These suspended houses are reduced to their simplest form both in conceptual imagination and in reality - the pentagon shapes look like children’s drawing of a house, and gable framing houses are one of the easiest structure to construct. These suspended spaces, therefore, become symbols of actual homes and aim to provoke the visitors to associate them with residential houses.

These house-shaped rooms are colored in bright yellow, red, and green corresponding to their sizes - the biggest spaces are yellow, the medium sized spaces are green, and the smallest spaces are red. Though the dimensions of the floating houses are fairly easy to tell from the ground, when visitors are inside of the scaffolding structures, the sizes of the houses become incomprehensible. The different colors act like codes for the visitors to understand the size of each suspended spaces, similar to the way people judge the social status of the owner in real houses by judging their size and condition.

Some of the “houses” have two entrances and each entrance directly connected with staircases, which made it easier for visitors to move through these floating interior spaces. Some of the houses only have one access to its interior, so these spaces have the potential to become more private. The bottoms, the sides and the roofs of the “houses” are solid materials, but the facades are made of translucent material. As a result, when visitors are inside of these floating “houses”, they can only see the apartment building behind the structure and the open space in front. They are hidden from other visitors in the floating spaces, and the higher they are, the more they can see outside of Tobacco Row. However, at the same time, they are partially visible for the visitors on the ground because of the translucent facade. Because of the construction of the floating houses, one is both visible and invisible inside the house. Visible because others can tell whether one is inside; invisible because others have no way of knowing what is happening inside the house. The floating houses in the scaffolding are toying with this paradoxical aspect of the home.

The house-shaped space in the structure is are only shells stripped of interior function. The lack of program within the houses has made the structure into a folly in the landscape - spaces of emptiness and uselessness. However, without utilities within the house, these spaces are no longer defined and therefore freed from the restraint of spatial organization of a traditional house.

The ground level of the plaza appeared to be a flat pavement at first glance. However, as visitors approach the site, they see multiple rectangular-shaped translucent glass floor on the ground indicating another level underneath the lawn. There are also several courtyards directing visitors to the underground.

As the visitors enter the underground level of the plaza, they are encountered with an open space with a seamless network of smaller rectangular rooms with different levels of enclosure. The underground space offers fluid circulation which the visitors are free to choose for themselves. There is no single entrance into the ground. One can either enter through one of seven courtyards, or one can enter through the staircase inside the scaffolding. The rooms inside are non-hierarchical - they are like objects distributed on a field. These smaller rooms provide different utilities such as toilets, washing and drying machines, stoves, ovens, sofas, televisions, dining tables, closets, and beds. Visitors can easily compare these small enclosed spaces with bathrooms, laundry rooms, kitchens, living rooms, and bedrooms. The courtyard in the context became gardens and provide light for the underground spaces. Some rooms have four solid walls surround the center utilities, whether they are toilet bowls or washing machines. These enclosed spaces seem more private, since they only have one door for each space, and only a few of them have windows. Some rooms are enclosed by both walls and columns. For example, the kitchen spaces usually comprise two sides of solid walls and two sides of equally spaced columns. The gardens/courtyards are enclosed by glass doors and walls. The more public rooms in the underground plaza allow visitors to experience different permeability of these public space since these rooms offer more fluid and blurred transition between inside and outside.

The concept of the underground plaza follows the idea of Jacques Derrida: in order to deconstruct the binary terms of “men belong to the public and women belong to the private”, the first step is to reverse the term occupying the positive position and the occupying the negative position. Here in the underground plaza, what’s considered to be private and feminine space is reversed to become public spaces. The second step is for the negative term to be “displaced from its dependent position and located at the very condition of the positive term (Rendell 2000, 104)”. Isolated from their context of the home, the rooms underground are operating independently and being placed in the public realm.

Terraformation of New Spatial Relation

If the scaffolding structure with floating houses is a comment on the appearance of the home as a symbol of social roles and relations, the underground plaza is a critique of the rigid program and dimension of the home. Together the project reveals the underlying absurdity in the idea of the home and encourages visitors to question what we consider to be normal. The social structure constructed and reinforced by the home should not be taken for granted. It is important for designers to realize that space can be used by the dominating class, race, and gender to make their privilege looks normal and natural. The project also encourages interaction - after all, it is not only important for us to question the social norm, but also to create new things which can break away from the existing social structure. This project, Reprogramming Domesticity, is a new kind of public realm which allows freedom and inclusivity.

Some of the floating spaces might become home for people who don’t own any property because they offer protected space and they are flexible enough to be converted into different things. Some of the floating rooms might be used for a community meeting because some of them are large enough for several people to occupy at the same time. People might just go up to one of the rooms for a view of James River. The underground space is similar in terms of its potential for diverse activities to happen. The garden and living room are more public for people to lounge in. The bathrooms are public bathrooms for anyone in need. The bedroom might just become a temporary hotel for an office worker to take a nap during lunch break. The kitchen can potentially be a place for community gathering.

By placing a project like Reprogramming Domesticity in an urban context such as Richmond, the project, therefore, has the ability of invite different social groups, who might not conform to the social norm, to inhabit and dwell the site. Because the programmatic function of the project cannot fit into any existing category of public space, it assumes much more potential than not only ordinary houses but also other kinds of public spaces such as plazas, parks, and squares. It becomes spaces in between - exist within the context of the site, but simultaneously outside of the conceptual boundary of the urban context.

Conclusion

Space is gendered and biased. It is important for designers to understand their designs are never value-free. However, there are moments “in a design that do allow for the possibility of inflection and variation represent potential sites in architecture where norms and their attending ideologies can be reviewed, resisted, and revised (Sanders 1996, 13).” Buildings or any kind of built environment are political and social because the way they organize people’s activities has “a profound ideological impact on social interaction - regulating, constraining, and (on occasion) liberating the human subject (Sanders 1996. 13).”

Responding to the opening quote of this essay, the value of a project like Reprogramming Domesticity is for designers to question the ability of architecture or any kind of space making, and hopefully acquire a sense of responsibility when thinking about the consequence of a design.

Bibliography

Sanders, Joel. Stud: Architectures of Masculinity. Princeton Architectural Press, 1996.

Spain, Daphne. Gendered Spaces. Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Rendell, Jane, Barbara Penner, and Iain Borden. Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction. Psychology Press, 2000

Urbach, Henry. “Agitate for Architecture.” Assemblage, no. 41 (2000): 81–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/3171341.